Flashback Fridays: Tripartite Government and Water

Three tiers of Australian Government were introduced at Federation in 1901. Previously there had been a cooperative of colonies under British rule.

The Australian Constitution specifically states that “the Commonwealth shall not, by any law or regulation of trade or commerce, abridge the right of a State or of the residents therein to the reasonable use of the waters of rivers for conservation or irrigation” (s 100). However, the State has ‘referred’ some control (under s 51xxxvii) over the Murray Darling Basin water resources through the Water (Commonwealth Powers) Act 2008.

The State moved to confirm the historical Common Law rule that property rights to resources found on ‘private’ land would not extend to ‘movable’ resources such as water, first in the unsuccessful Water Supply (Wells and Tanks) Bill in 1891 and then in the subsequent Rights in Water and Water Conservation and Utilisation Act 1910. The latter Act included similar language to the Water Act 2000 that “all rights to the use, flow and control of all water in Queensland are vested in the State” (s 19).

While the State has full power and responsibility over water resources, many powers are delegated to Local Government. Although Local Government does not have constitutional recognition, it is recognised under a raft of paralegal documents and policies, particularly with respect to its “significant environmental responsibilities, such as approval of applications for development, water supply, sewage and stormwater” (Bates, 2002).

Local authorities in Queensland have existed under a range of names from the early Municipalities and Divisions through different types of councils to the modern Aboriginal, Regional and Shire councils. The terms Municipality, Council and Local Government are used interchangeably in this post except where specified.

Queensland was the only Australian colony that commenced (after separation from the NSW colony in 1959) with its own parliament instead of first spending time as a Crown Colony. By this time, Western Australia was the only Australian colony without responsible Government. The terms State Government, Colonial Government and Queensland Government are also used interchangeably.

In Brisbane, the Government formed the Brisbane Waterworks Commission in 1863 at the request of the Municipal Board but then imperiously selected its own Commissioners, including only a single Municipal Alderman (the Brisbane Mayor). In the ensuing period of indignation from the Council, the Brisbane Courier reported “the new Board will be a farce, and another example of the disregard to the interests and wishes of the public, which has long distinguished the policy of the present Government.”

This criticism of the high-handed approach of the Government, which likely reflected concern over the Municipality’s ability to manage the waterworks, seems overly harsh given the “present government” had been in existence for less than three years. Moreover, a similar governance model had been adopted for the Yan Yean Dam built in 1857 to supply Melbourne as well as in other early Australian infrastructure projects.

In any event, the new Commission prevailed and went on to oversee the selection, design and construction of Australia’s second major water supply. The resulting Enogerra Dam was completed in 1866 and was twice the height of Yan Yean.

The Brisbane Municipality was further outraged when the Brisbane Board of Waterworks was formed by the State to manage the ongoing operations of Enoggera rather than transferring this role to the Council as had been expected.

In another parallel, the same situation had arisen at the completion of Yan Yean and as in that case, a political stoush ensued. For Queensland this was complicated because the Local Board could not legally assume the debt raised by the Queensland Government and “moreover, the government had grave doubts about the ability of the Council to manage such a large financial asset” (Whitmore, 1997). Relative peace was achieved when the membership of the board was reconstituted and legislation passed allowing Local Boards to transfer needed powers to a board of waterworks.

These disputes were clearly instructive for the young and still financially insecure Queensland Government. In 1865, a Department of Harbours and Rivers was established under the Treasury and assumed responsibility for future water infrastructure development, but it was disbanded amid a financial crisis for the early Government one year later.

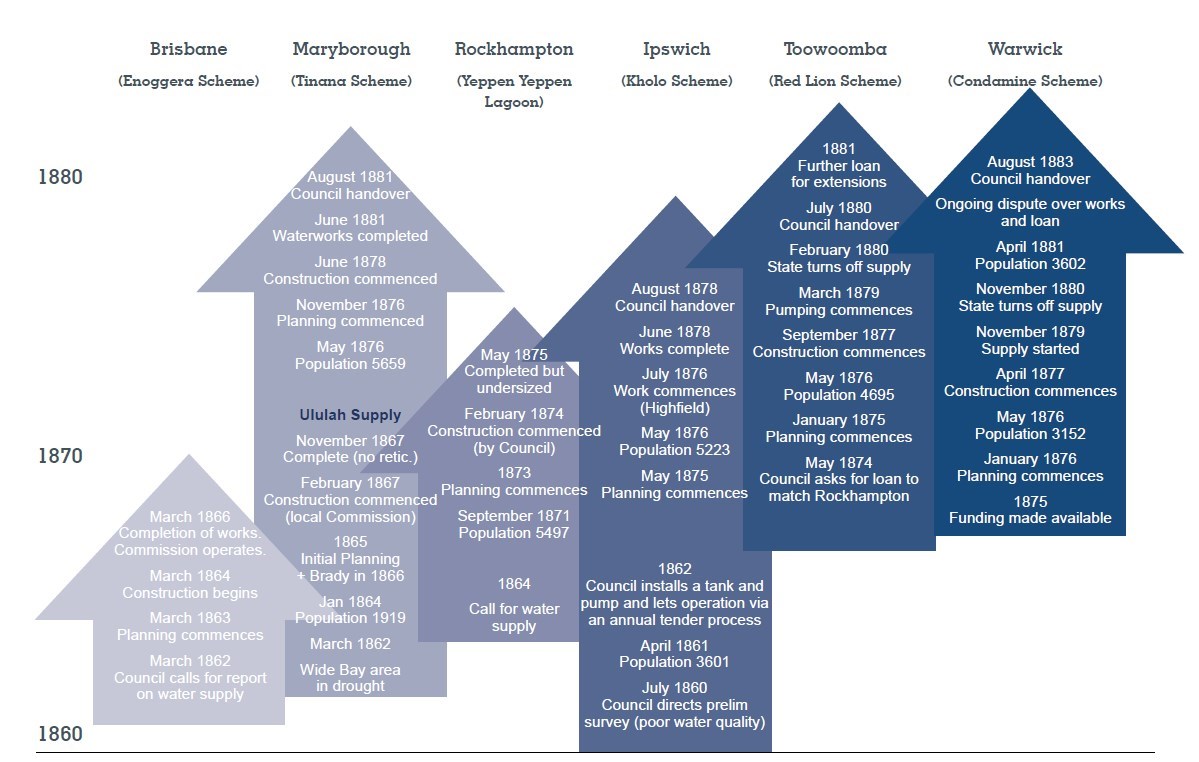

During this time however, a ground-breaking survey was undertaken for water supplies for Ipswich, Toowoomba, Warwick, Maryborough, Rockhampton, Gladstone, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville and Dalby. The report on the survey was completed when stability was regained in 1868.

Also during this period, the Queensland Government funded, designed and built its second major water supply. The Ululah Dam in Maryborough caused repeated tension between the State and Maryborough Municipality, and ended up undersized with no reticulation, but it serviced the community from 1867 via private water carters.

The negative experiences with Brisbane and Maryborough Municipal Boards along with the cost estimates provided by the statewide survey may have been sufficient to convince the Government that a new approach was needed. This need was reinforced by pleas from many other regions to address water supply issues and to provide funding to match that loaned or spent in other areas.

In 1869 dramatic legislation was introduced into parliament “giving the responsibility for the construction of all future waterworks in Queensland to a colonial water board. The Bill was strongly resisted in the Legislative Assembly and it was subsequently withdrawn” (Whitmore, 1997). Had the legislation been created, Queensland may today have a single water service provider similar to other states in Australia.

It was not until 1874 that a compromise was instigated through the creation of the State Public Works Department which would oversee loans, design and construction of regional waterworks. The infrastructure and loans would then be handed over to Municipal Boards that would manage the schemes and collect rates to repay the initial loans.

A period of rapid development ensued with waterworks installed in Toowoomba, Warwick, Ipswich and a second scheme in Maryborough at Tinana. In contrast, Rockhampton had jumped the gun, receiving a small loan in 1873 soon before the Act was passed, and proceeded to develop its own supply following an extremely pared-back version of the State’s recommended design.

Unfortunately, this and many of the State Government-led schemes developed over the following six years were plagued by unrealistic resourcing, lack of local information, communication breakdown between the two levels of Government and unrealistically ambitious and optimistic timeframes and expectations. Similar criticisms could be levelled at the development of the SEQ Water Grid from 2008 (too many perhaps, with the exception of insufficient resourcing).

With these challenges, it is remarkable the early schemes were completed at all given the rudimentary experience, structures, local information and relevant skills in Queensland at the time. Predictably, many of the completed schemes required improvements, repairs and extensions after being completed. This generated significant friction between the Queensland Government and the Municipalities.

The Warwick scheme was completed in 1879 but the Municipality refused to accept handover of the infrastructure and the debt because of cost overruns, an undersized reticulation system and a leaky reservoir. The State shut down the supply at the end of 1880 telling the Local Government that interest from their debt would continue to be deducted from their regular annual endowment. This tactic had already been used successfully by the State when Maryborough and Toowoomba refused handover because of the cost blow-outs of their schemes. Maryborough quickly re-negotiated and in Toowoomba the State turned off the water for six months before the Municipal Board capitulated.

However, Warwick was smaller and had a relatively good natural supply supplemented by individual rainwater supplies which were of good quality because of the accessibility to galvanised iron delivered by the new railroad. There had in fact been little community demand for a waterworks prior to the State making initial funding available as part of the statewide response. Warwick held out almost three years.

In early 1882 the State offered a Relief Bill that proposed rescinding the debt but leaving the State responsible for the waterworks including any income. Whitmore (1995) reports:

“The Council agonised over its reply, the problem being that [Premier] McIlwraith refused to give any indication of the size of the water rate that the government was likely to impose. Moreover, councils that had already taken charge of their waterworks were managing quite well and even making a small profit out of their water rates and some Warwick Aldermen felt that they could run the enterprise more cheaply and efficiently than the Government.”

In the end, the proposal was unsuccessful, but the plant was handed over in August of the next year regardless. The State and Local Governments had renegotiated the costs and the State had guaranteed infrastructure of ‘sound condition and good working order’ and agreed to reimburse the lost endowment payments.

This tumultuous period of rapid but ‘under-cooked’ development and the repeated clashes between State and Local authorities was partly a response to the authoritarian approach of the Queensland Government and the disorganisation of the new Municipalities. However, other factors were also critical, including the lack of knowledge of local conditions, and limited engineering and administrative skills resulting from the lack of funding in the early authorities.

As always, clashes between individual personalities and egos were responsible for some of the poorer decisions but it is clear that these energetic individuals also drove the development of the early water industry that underpinned growth across the State.

Timeline of development of the first Queensland water supply schemes following separation from NSW.

Feature image: Mt Crosby Weir Construction 1925, courtesy Mt Crosby Historical Society

Back to list